Not all fabrics are created equal, especially as regards the costs of production (consumption of resources, risks to human health, resultant release of persistent contaminants, and subsequent harm to ecosystems) and the costs of disposal (product life expectancy, leaching of toxic components during decomposition, and whether some or all of the constituent materials can be recycled).

This guide to sustainable fabric will explore these differences in detail, giving you the confidence to vote for with your dollar and make more ethical purchases.

By Ellen Rubin

An Introduction: The Need for Sustainable Fabric

Trying to live sustainably is complex. There is so much information out there, yet much of it seems contradictory and there’s just a lot of it to wade through. Sometimes, you have to pick the areas that have the greatest impact on your life. Fabrics and textiles surround us – from what we wear to our bedding and towels, to our home décor. This guide is an attempt to examine the factors that make a fabric sustainable.

It’s important to remember that nothing is perfect, and even though it would be easiest to just walk into a store and buy what looks prettiest, or feels the best, these choices may not be sustainable. There are usually better choices to make that in the long-run will be beneficial to your and the planet’s health. Being thoughtful and discriminating about what and how much you buy is the best way to be sustainable.

Why is it important to Make Fashion and Fabrications Sustainable?

Every fabric must be sourced from raw material, through production, and eventually will be discarded. How much environmental damage it causes adds up at each stage. It’s easiest to let the statistics speak for themselves….

Size of the market:

- The global apparel market was worth $1.9 trillion in 2023 and is predicted to reach $3 trillion by 2030. The US market share is the largest at 20.2%.

- The home bedding market was worth $104.64 billion in 2023. It’s expected to grow 7.4% from 2024 to 2030.

- In last 15 years, the fashion industry has doubled its production with many fast fashion companies showcasing 10 new collections per year instead of 2.

- 80-100 billion new clothing garments are produced annually, a large percentage remain unsold and go directly to a landfill.

- 92 million tons of textile waste are produced every year. Only 20% of discarded textiles are collected for reuse or recycling. Of the rest, 66% end up in landfills, 19% is burned, and 15% is recycled.

Environmental impacts…air and water pollution:

- Carbon emissions:

- The fashion industry is responsible for 10% of all global carbon emissions/greenhouse gas emissions or 10 billion tons. This includes sourcing materials and supply chains to washing and waste.

- The European Environment Agency has determined the 270kg of CO2 emissions are generated per person through textile purchases.

- Plastic pollution from synthetic fabrics

- Since the 1950’s, plastic pollution attributed to polyester clothing has been estimated as 5.6 million tons.

- 1.3 billion barrels of oil are used each year to manufacture new clothes.

- 200,000-500,000 tons of microplastics from textiles enter the global marine environment every year. (EEA.europa.eu)

- It takes at least 200 years for a synthetic garment to decompose.

- Textile production produces 42 million tons of plastic waste per year. Clothing packaging produces even more.

- Water pollution

- Textile manufacturing is responsible for 20% of the planet’s wastewater pollution.

- The dumping of toxic chemicals used in manufacturing and dying fabrics has made large sections of major rivers like the Citarum River in Indonesia and Pearl River in China uninhabitable for fish and animals. The Citarum is the most polluted river in the world.

- The International Cotton Advisory Committee (ICAC) has determined that to produce 1 kg of cotton lint or enough fiber to produce 1 t-shirt and a pair of jeans, uses 1,931 liters of irrigated water and 6,003 liters of rainwater.

- The Aral Sea has been shrinking since water was first diverted in 1960 for irrigation. It used to be the 4th largest inland body of water yet has shrunk to less than ¼ of its former size and is now 3 small separated lakes, one of which has periodically dried up completely since 2010. It used to have a surface 175 feet above sea level and covered 26,300 square miles (270 miles x 180 miles) with a depth of up to 226 feet deep. In 1992, the two main parts covered 13,000 square miles and was only up to 50 feet deep.

It’s obvious that fabrics and the fashion industry are major contributors to the environmental crisis. In addition to buying less and being conscious of how we dispose of unwanted clothing, it’s also important to become aware of what we are buying and its level of sustainability. At the lowest common denominator, not all fabrics are created equal.

What makes a Fabric Sustainable?

The sustainability train can derail at any stage in the trip from raw material, to your doorstep, to the discard pile.

The best choices are sustainably created, easy to wear, care for, and discard. We’ll look at different types of fabrics and discuss the pros and cons of each. What does it take to create the fiber? Is it energy and/or water intensive? Are there dangerous chemicals involved? How easy is it to care for the fabric or does it need to be dry cleaned? What happens when you’re done using it…can it be easily recycled or will it decompose naturally and quickly?

The fabrics themselves are the foundation of any garment regardless of whether you are wearing a plant-based fiber (cotton, hemp, linen, bamboo, etc.), an animal-based fabric (wools, silk, and leather), or a synthetic (polyester, acrylic, nylon), there is energy used to produce it, CO2 emissions, chemicals for dyes and manufacturing, and then disposal issues.

Sustainability can happen, or not happen, at each stage in the process. Additionally, there are ethical issues of human and animal treatment that are of primary importance to some consumers.

Even shopping online, it’s incredibly difficult to determine how sustainable a garment is.

We can read websites about sourcing and processes, but it’s easy for companies to use confusing language or greenwashing to befuddle buyers. Merely seeing words like “natural” or even “organic” doesn’t ensure that what you are purchasing really is sustainably made.

Perhaps it’s better to rely on some generalities about what types of fabrics are more likely to be sustainable. We can only use our best efforts because every garment, even using the most sustainable fibers, can become unsustainable depending on how it’s treated, manufactured, or disposed of.

Knowing the most likely sustainable fabrics helps, as does some shortcuts in the form of reputable certifications. So, where applicable, along with each fabric discussed, I’ll list some certifications to look out for. Overall, if you see the following, you can be pretty sure they are sustainable:

- B Corp

- Cradle2Cradle

- Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS)

Fabric and Clothing Disposal

Before we start talking about the characteristics of individual fabrics, we should talk about fabric waste.

Clothing that has been bought can be thrown out to be added to landfills or incinerated, sold or donated to be reused (upcycling), or sent for recycling.

Textiles manufacturers can have unsold bolts of fabric (deadstock) and manufacturer have unsold items or fabric scraps that need to be sent for recycling or disposed of. All of this has to go somewhere and if it isn’t recyclable, biodegradable, or compostable, it’s going to be around for a long time.

The extent of textile waste (everything that isn’t currently in someone’s closet) is extensive:

- 40% of every bale of manufactured textiles end up as waste.

- 92 million tons of textile waste are produced and end up in landfills every year from the 100 billion garments that are produced.

- The average American throws away 37kg/81.5 pounds of clothes every year which equals 11.3 million tons of waste in the US.

- 60,000 tons of unwanted fast fashion is illegally dumped every year in the Atacama Desert of northern Chile. Most recently, 100,000 tons of clothes were burnt. Much of this was polyester, so when it burned, the surrounding air quality deteriorated to the point of toxicity. There are similar dump sites in India, Guatemala, and Accra, Ghana where unwanted new clothing and second-hand clothing is dumped. It’s estimated that 6-12,000,000 garments pass through the market in Ghana per week with 40% discarded as waste.

- 84% of all donated garments end up in landfills and incinerators.

- Only 1% of discarded clothing is recycled into new garments.

Fabric Characteristics

Photo by Cindy C on Unsplash

Synthetics Made from Fossil Fuels

Synthetic fibers are petrochemical byproducts that are responsible for more than half of all fiber production. You’ll find it listed on the labels as either the primary fiber and a blend under names like polyester, elastane, nylon, Lycra, or acrylic. The quantity manufactured has doubled since 2000 and is predicted to grow to almost 75% by 2030.

It’s pretty impossible to consider anything plastic as sustainable but some types are more so than others, and some types of synthetic fabrics can be recycled.

Each fabric in this grouping has some unique characteristics and purposes.

- Nylon was the first fully synthetic fiber and is silky, yet abrasion- and wrinkle-resistant. It’s durable, moisture wicking, and is recyclable.

- Polyester is wrinkle-free, water-repellent, lightweight, yet strong. It’s the underlying fiber in fleeces, yet can be sleek enough to be a silk substitute or lining material. It’s generally not breathable but is moisture wicking so it will dry quickly. It’s not infinitely recyclable.

- Acrylic is often used as a wool substitute in knitted materials because it’s lightweight and hydrophobic but it isn’t as warm as wool and is highly flammable. It isn’t recyclable.

- Elastane, the generic term for Lycra and Spandex, is generally the stretchiest of these fabrics. It has limited durability but is moisture wicking and may be breathable, depending on the weave. It’s used in undergarments, swimwear, and athletic wear. It isn’t currently recyclable.

Before the late 1930’s, synthetic fabrics didn’t exist. Their popularity started overtaking natural fibers in the 1950s because it is the least expensive fabric to produce, as well as being machine washable, shrink and wrinkle resistant, and it can be formed into just about any texture and weave from very thin to very heavy.

It can be made to stretch, be shiny and slinky, or can be weather- and wind-resistant. Unlike natural plant and animal fibers which are dependent on harvests, weather conditions, and agricultural workers, synthetics are always in ready supply.

The environmental impact of synthetics include:

- The fashion industry uses 70 billion barrels of oil every year to make fabrics.

- 1 ton of plastic generates 2.5 tons of CO2.

- Plastics, including synthetic fabrics often contain toxic chemicals like BPA and PSAF (forever chemicals).

- A single synthetic garment can release up to 1.7 grams of microfibers or 700,000 microscopic beads of plastic per wash cycle. These enter our water systems and pollute our rivers, lakes, oceans, and drinking water. There is an estimated 5.25 trillion macro- and microplastics in the ocean which finds its way into our seafood.

- Synthetic fabrics aren’t compostable and generally aren’t biodegradable. They will sit in our landfills for at least 200 years.

While some synthetics are recyclable, none are biodegradable. It’s been argued that recycling is the solution to the polyester problem of making synthetics more sustainable. This is deceptive. Yes, recycled polyester uses 62% less energy, 99% less water, and produces 20% less CO2 emissions than virgin polyester, but the overwhelming majority of polyester is still made from virgin material.

Only approximately 9% of the synthetic garments being made use recycled fabrics that are sold under names such as rPET or Repreve®. Of that 9%, 93% comes from plastic bottles and not recycled textiles.

While PET, or the plastic from bottles, can be recycled 5 or 6 times, the technology hasn’t been developed that makes recycling synthetic fabric practical. Recycled nylon from ocean waste, branded as Econyl®, is another popular choice.

What current recycled synthetic fabrications enthusiasts ignore is textile manufacturing waste, unsold, overstock, or second-hand garments that either go directly to landfills where synthetic clothing will sit for centuries or be incinerated and release toxic gases.

The only way polyesters can become even remotely sustainable is if no virgin materials are used. Scientists need to devise a way to break down synthetics into other usable, non-toxic elements, and an efficient and practical system to separate and reuse blended materials. Research is ongoing and promising.

Currently, the large percentage of blended cotton/poly fabrics that are made and sold are no longer biodegradable (because of the polyester content) or easily recycled because of the mixed threads. This may change in the near future; new technologies are being developed that can separate the two materials using water, heat, and non-toxic chemicals in an inexpensive process. This doesn’t eliminate the current problems of manufacturing and waste, but it does give us hope for the future.

One final note about plastics: almost every garment contains some polyester elements even when the garment isn’t described as a synthetic. Buttons, zippers, thread, and labels are almost always made of plastics or polyester even if they aren’t listed on labels or on website descriptions.

There are a few manufacturers who strive to eliminate these plastics. Zippers could be metal (although the tapes are still polyester for durability and maintaining shape), buttons can be metal, shell, horn, corozo, coconut hull, or tagua nuts, and labels can be made from plant-based fabrics or printed directly on the garment. Polyester is still the best source of thread because it can be made in a single long filament, has greater tensile strength, and doesn’t fray in machines.

Plant-Based Fabrics

Cotton

There is no single sustainability title you can give cotton. It ranges from completely unsustainable to very sustainable. After synthetics, cotton is the most widely used fiber in fashion. Cotton’s appealing because it is soft, very comfortable, holds dye really well, and is versatile.

It’s the foundation of t-shirts and jeans, as well as dress shirts for men. It can be knit for stretch or woven for a more finished and structured look. It can be cool, although it tends to hold on to moisture, so you can feel clammy. It is also compostable and biodegradable.

Cotton is certainly a fabric staple that is here to stay. The question becomes how to make the best choice of what’s available.

At the sustainable end of the spectrum is regenerative farming of organic cotton, but only approximately 1.4% of the world-wide harvest is organic. If properly farmed, most of the cotton plant can be utilized in some way and organic cotton doesn’t rely on chemicals or irrigation. If you are concerned about the environment or the chemicals you come in contact with, buy organic cotton.

On the opposite side of the spectrum is uncontrolled cotton providers where environmental damage, heavy chemical usage and unfair labor practices may be the norm. Cotton has earned the title of “the dirtiest crop on earth” because it requires more chemicals to grow than other plant-based fabric.

The amounts are staggering: cotton growing uses 15% of all pesticides, 25% of insecticides, and 6.8% of all herbicides consumed across all types of agriculture.

Growing cotton depletes the soil of most major nutrients. Replacing those nutrients with chemical fertilizers harms the soil: it affects the ability of the soil to filtrate water and sequester carbon, as well as damaging its natural fertility. Growing one ton, or 907 kg, of cotton, required 18 kg of potassium, 32 kg of nitrogen, 11, kg of phosphorus, and 2.7 kg of sulfur.

Rather than following regenerative agriculture practices, most cotton growers are more interested in the least expensive and fastest way to grow and harvest large crops. They use defoliating chemicals to mechanically harvest the cotton boles instead of hand picking the cotton.

Hand harvesting produces longer, softer fibers and reduces energy consumption by 60% and lowers CO2 emissions. It also preserves the plant so that it can bloom again, rather than killing the plant to get the boles. This is the trade-off between labor costs vs. ecological cost.

The chemicals used not only impact soil quality and deny the soil of nutrients when the plant eventually returns to the soil, but the chemicals stay in the cotton and can’t be washed out. If you want to learn more about the environmental cost of cotton production you can visit sites like The World Counts.

One of the biggest complaints against cotton sustainability is its excessive use of water. The draining of the Aral Sea is attributed to cotton production. Cotton cultivation accounts for 11% of all freshwater agricultural usage even though only 2.5% of cultivated land is devoted to cotton. Even worse, 66% of cotton harvested is not suitable for fabric production and becomes agricultural waste.

In addition to the water-intensive growing cycle, the manufacturing process is water intensive and environmentally damaging. It takes 10,000 liters of water to create a single kilogram of cotton fabric. That translates to 700-1,700 gallons of water to create a t-shirt, and 3,781 gallons to create a single pair of Levi’s.

Harsh bleaches and dangerous dyes, such as Azo dyes, are often used, many of which are carcinogenic and waste water is directly dumped into local waterways. The documentary RiverBlue chronicles the polluting of 70% of the rivers and lakes in China by the textile industry by dumping 2.5 billion gallons of manufacturing wastewater.

If you are concerned about ethical treatment of workers, cotton doesn’t have a good record. Many areas, like Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and the Xinjiang and Uyghur regions in China which produce 20% of all cotton fabrics and clothing, rely on forced/slave/child labor to grow, harvest, and manufacture cotton clothing.

Photo by cottonbro on Pexels.com

I don’t want to give the impression that all cotton is bad. There are some regions that produce very fine organic (whether it has the official certification or not) cottons without relying on all the bad stuff. You can even get natural cotton in a variety of colors such as pinks, green, beiges, tans, and pure white that have not been treated or bleached in any way. There are companies that pride themselves on creating sustainable, ethically, and environmentally responsible regional farms that produce high quality cotton garments.

While the companies that pride themselves on their sustainability practices probably tout their farming, manufacturing, and distribution systems on their websites, not every company does so, and you can’t always check on these things when you are shopping in-store. This is where knowing what some of the important labels and certifications mean, especially when it comes to shopping cotton garments.

- Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS) is the easiest way to ensure that the cotton you are buying is sustainable. Seeds can’t be genetically modified and the cotton has to meet strident standards both ethically and ecologically for the entire supply chain. Certification indicates that there hasn’t been excessive irrigation and you don’t have to worry about any toxic

chemical usage. (Note: some basic fertilizer chemicals, like potassium, can be used and still have a product meet organic standards.) Organic cotton uses 91% less water, 62% less energy, creates 42-46% fewer CO2 emissions, and causes 26% less soil erosion.

- Organic Content Standard (OCS) traces organic fibers from the farm to the final product.

- OEKO-TEX is an independent global testing and certification system across all processing stages. They certify every type of textile and leather for sustainability and transparency. Their Made in Green label is granted to “products that have been manufactured in environmentally friendly facilities under safe and socially responsible working conditions.” Their Standard 100 label is granted to textiles that have been tested for harmful substances. Every aspect of finished garments from thread and buttons to fabrics are tested. They have a separate label just for cotton.

Recycling of cotton fabric does exist, although in very small quantities. It’s more sustainable than virgin cotton and prevents some waste going to landfills even though it still requires some chemical, water, and energy usage, and the addition of more dye to even out the color.

Recycled cotton is usually blended with another fiber such as polyester because recycled fibers are not as durable as its original textile. It’s currently an expensive proposition and cotton can only be recycled once for it to maintain its integrity as a usable fabric. It’s important to remember that as soon as cotton is blended with another fabric, it becomes unrecyclable, for all practical purposes, until technology in that area improves.

Bast Fabrics: Linen, Hemp, Jute, Ramie

The most sustainable fabrics are made from the bast, the inner bark, of the flax, hemp, jute, and nettle plants. None of these plants require fertilizer, pesticides, or extensive, if any, irrigation. Another advantage to growing bast plants is that every part of the plant is usable for an extensive number of purposes from packaging and building, to foods and medicines, to even creating bio-plastics used in automobiles. All four of these ancient plants are the cornerstones of economies in different parts of the world.

The fibers used to make cloth can be retted, or separated from the plant, through water processing so no major chemicals are needed to produce the yarns. Some producers use chemical retting, which is not as sustainable.

Not all four fabrics are as readily available as others such as cotton or polyester, but, because of their sustainability, they are becoming more popular. Until recently, cultivating hemp was illegal in the US, but its acreage is increasing. Luckily, it’s always been grown in other parts of the world. China is the largest producer at 30%, followed by Canada, and Europe. It’s produced in over 32 countries because it is so easy to grow and so useful.

Photo by Madison Inouye on Pexels.com

The largest producers of linen are Europe (especially Ireland, Italy, and Belgium), China, and the US, and both supply and demand are growing. Jute is produced primarily in Bangladesh and parts of India. We are more familiar with its rougher form of burlap, but it can also be made into fine fabrics that resemble silks. Ramie is produced in China, Brazil, and the Philippines.

Regardless of sustainability, no one wants to wear something if it’s uncomfortable. Luckily, most bast fabrics have many positive qualities. They are extremely breathable, wick moisture away from the body, yet can absorb large quantities of moisture without feeling clammy, are very sturdy, and even thermoregulating so you are more comfortable summer and winter.

For instance, hemp has 3 times the tensile strength of cotton. Hemp, linen, and jute are bacteria- and mold-resistant, UV protective, and anti-static. They aren’t initially as soft as cotton or polyester, but improve as they age. Yes, they will wrinkle more. They can easily be blended with other fabrics if you are looking for something that is more drapey. You should be able to hand or machine wash all these fabrics.

Photo by Washarapol D BinYo Jundang on Pexels.com

You can feel good about buying these fabrics because they actually improve the environment. Hemp removes 1.63 tons of CO2 from the atmosphere per ton of growth and jute will absorb 15 tons of CO2 and release 11 tons of oxygen in the 120-day growing period before harvest.

All these fibers improve soil quality by removing toxic chemicals and replacing nutrients. It’s also possible to grow much larger numbers of bast plants per acre than other crops such as cotton. Growing seasons are short – as little as 3-6 months until harvest and crops such as jute can rotate with rice crops for a regenerative farming cycle. Again, these crops don’t need chemical fertilizers, pesticides, or extensive irrigation.

They all produce very strong fabrics so your clothing will last a long time, yet they are easily biodegradable.

While you can look for items that are GOTS (organic) certified, most likely, just due to the nature of the fibers used, your garment will be more sustainable than most other choices. It’s only when manufacturers use unsustainable dyes, packaging, or shipping practices that you have to worry about harming the planet.

Semi-Synthetic Plant-Based Fibers: Viscose, Raylon, Modal, Cupro

There is a group of fabrics that fall somewhere between plant-based and synthetic called man-made cellulosic fiber (MMCF). They use plant matter but require chemical processing to form usable threads that can be woven into fabric. The cellulose fibers from bamboo, beech, birch, oak, pine and eucalyptus trees, and byproducts of cotton seeds, fall into this category. They don’t all have the same level of sustainability.

Rayon is the generic term used for fabrics made from wood pulp and was the first fabric to be developed, and was patented in 1855 as a silk substitute. Cellulous or wood pulp is put into a “chemical soup” that softens and it breaks down then extrudes longer fibers that can be woven into fabrics. Modern iterations of rayon include: viscose, acetate, Modal, Lyocell, or Tencel.

Some are propriety names, others refer to more refined, versions of rayon. MMCFs are gaining in popularity because they are versatile, often used for outdoor or athletic gear, breathable, wrinkle-resistant, safe for sensitive skin, absorbent, moisture wicking, durable, and soft. They are generally recyclable and biodegradable. They currently account for 6% of all fiber production.

Sustainability is dependent on the type of wood pulp used and its sourcing, as well as the chemical processing systems used. Factories are often located outside the US and Europe where safety regulations are more lax, because the chemicals involved can include caustic soda, ammonia, acetone, sulfuric acid, carbon disulfide, chlorine, or sodium hydroxide.

Ecologically responsible factories, like Lenzing of Austria, makers of Ecovero™, Tencel™, and Veocel™, use the least caustic chemicals, have a closed-loop process that recycles almost all the chemicals, and responsibly disposes of their waste to keep chemicals out of waterways.

All three of these fabrics are among the most sustainable fabrics made. They also take all necessary precautions to protect their workers. Unfortunately, this can’t be said of all factories where health impacts such as heart disease, birth defects, cancer, and skin conditions which afflict workers and surrounding communities and can be attributed to chemicals used.

The other important sustainability issue associated with MMCF fabrics is the source of the wood pulp. If you get the wood from an old-growth forest, it will take at least 20 years for new plantings to reach maturity. Not considering erosion, replanting just can’t equal the carbon sequestering that old growth forests are known for. Yes, trees are considered renewable resources, but they aren’t replaceable in the short-term like bast plants which take only a few months before harvesting.

Bamboo is among the fastest growing plants in this class of fabrics. It takes only 5-6 years before it can be harvested. Eucalyptus is another fast-growing plant. However, beech and birch trees are slow growers and take 30-50 years to reach a mature height. Therefore, the more sustainable choices in this category are bamboo or eucalyptus. In addition to speed, bamboo thrives with little in the way of water, fertilizers, or pesticides. The root systems continuously send up new shoots so the plants themselves don’t need to be replanted after harvesting.

The best certification to look for is the Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC) seal of approval. Also look for this seal on your packaging materials to ensure paper and wood products have been sustainably harvested.

There’s one other textile that can be considered in this class of fabrics, but it’s made from the linter, or fuzz, around cotton seeds rather than a wood pulp. It is still plant-based, but requires chemical processing. Cupro is often used as a polyester or silk substitute, especially for linings. It’s very silky, yet breathable and recyclable. The largest brand name of cupro is Bemberg, manufactured by Asahi Kasei. This is a great alternative to polyester and definitely something you should look for in any fine lining.

Animal-Based Products

This group of textiles includes wools, leathers, and silk. Again, sustainability ranges from very sustainable, to horrible. There are also many more ethical concerns that may factor into your decision. You can look for certifications by:

- Textile Exchange Certification like the Responsible Down, Mohair, or Wool Standard

- PETA

Some wool textiles are inherently more sustainable because the animals the fibers come from place less strain on the environment. When compared to a synthetic counterpart, for instance acrylic vs. wool, the wools will generally be more sustainable because there is less water usage and chemicals involved, and they can be recycled, are bio-degradable, and compostable.

Alpaca, Llama, and Camel Hair Wools

Photo by Trace Hudson on Pexels.com

Alpacas, llamas, and camels are indigenous to areas with extreme climates and marginal land that wouldn’t support organized agriculture.

They feed on native grasses without depleting the resource because they eat the tips rather than ripping grasses up by the roots, need little water, and cause very little soil damage due to their large, soft foot pads. It’s these same extreme weather conditions that make these such great wools to wear. They’re warm, temperature regulating, and breathable.

Their fleeces are harvested without harming the animals because they are either naturally shed or can be easily and safely sheared. In fact, many camel herders merely travel with the pack and pick up whole swaths of shed wool. These animals also yield more fiber per animal than some other wools so fewer animals are need.

These wools don’t require much in the way of processing so little energy or water is needed. The wool is washed with mild soap, combed, and spun, without chemical additions. The wools come in a variety of shades. Alpaca and llamas range from white to black and almost every shade of brown.

Clothing made of llama wool is not as common as alpaca. Camel hair ranges from dark brown to cream. In addition to traditional herders, alpacas and llamas are ranched commercially throughout the world.

Sheep Wool

Photo by Dan Hamill on Pexels.com

There are more than 200 breeds of sheep, some provide better raw material for textiles than others. In 2022 almost 1.3 billion head of sheep were raised worldwide. Australia leads world production of wool accounting for about 25% overall, and 50% of the Merino wool. China, the United States, New Zealand, and Argentina are the other leading producers.

Unless it is organic or a product of regenerative farming, wool isn’t particularly sustainable to produce, even though many consider it a renewable resource. Note: There do exist some farms and small enterprises that produce very fine sustainable sheep wools. We are talking about the large commercial sheep farms.

There are innumerable ethical questions about industrial sheep-farming practices. Some countries, such as New Zealand, have outlawed “mulesing” which many consider an inhumane practice in shearing. There are also outcries that overall, sheep are treated with cruelty.

There is also ample evidence that animal agriculture is environmentally destructive: sheep herds are responsible for 18% of human-caused greenhouse gases and are second only to cattle in methane emissions. The carbon footprint of the wool needed to make a sweater is 27 times higher than if the same garment was made from cotton. The amount of land needed to produce a single bale of wool is 367 times the amount of land needed to create a bale of cotton.

Both cattle and sheep farming require excessive amounts of water, land, and grain to feed the herds. Sharp hooves and overgrazing lead to land degradation (desertification), erosion, and the loss of biodiversity. Animals also create a great deal of waste that degrades soil quality and contaminates waterways.

The overabundance of nutrients, or eutrophication, from sheep farming significantly and negatively impacts local freshwater sources. With judicious management, most of these negative impacts can be averted, yet industrial farming, the need for cheap raw materials, and the quest for inexpensive and abundant fast fashion often means that expediency wins over sustainability.

The processing of wool from raw material to the knits in your closet is another cause of unsustainability. Sheep are dipped in insecticides and fungicides to prevent parasites. It helps keep the herd healthy, but the chemicals stay in the fleece.

Sheep wool is naturally coated with lanolin oil that must be removed before it’s processed. Chemicals are used to strip the “greasy” substance, and the washing in very hot water uses even more resources. Sheep hairs are covered with scales or barbs that may be chemically smoothed to make the wool gentler on the skin. Dying may use heavy metals such as chrome.

None of this means that wool has to be unsustainable, it just means you have to be discriminating in what you purchase. Look for the following certifications, in addition to B Corp and GOTS certified garments, to help you find sustainable wool products:

- The Responsible Wool Standard (RWS)

- Woolmark Certification

- ZQ Merino

- Certified Organic Wool

- Certified Animal Welfare Approved

Wool is a fairly sustainable material once it’s been processed and manufactured because it’s very durable and odor resistant, so it requires infrequent hand washing and line drying. At the end of its life, wool is recyclable, bio-degradable, and compostable. For recycled wool garments, look for:

- Recycled Claim Standard (RCS)

- Global Recycled Standard (GRS)

Cashmere

Photo by Guduru Ajay bhargav on Pexels.com

Cashmere is sourced from a variety of goat breeds that live primarily in the highlands of central and south Asia (Tibetan plateau, Outer Mongolia, China, India), although there are also herds in Australia and New Zealand. Many of the same factors that make influence sheep wool sustainability apply to cashmere.

Properly managed, it can be sustainable. Unfortunately, demand for this luxury item and affordable prices has led to unsustainable practices that are becoming the norm.

There are approximately 700 million cashmere producing goats worldwide.

Although China only raises 120 million goats, it is responsible for 70% of the fashion produced. The shortfall is made up by imported raw material. Both raising the goats and processing the wool are environmentally stressful. Goat methane emissions are similar to sheep. There are also similar claims of animal cruelty and unethical practices associated with goat hair harvesting.

The fibers used to make fabric comes from the inner coat, and while it doesn’t have to be painful for the animal, modern practices focus on speed and expediency rather than traditional means of gently combing the hair.

The least sustainable aspect of goat herding is the impact on the land. Goats eat a lot, 10% of their body weight daily and require lots of water and grazing space. In comparison, alpacas eat 1-5% of their body weight and require little water.

Goats also rip plant matter from the roots and their sharp hooves degrade the soil and cause erosion, so that unless the herd is moved frequently and grasslands are left for long periods of time to regenerate, desertification quickly occurs.

Over-grazing now threatens 90% of Mongolia. There are also similar issues of waterway contamination from eutrophication and waste toxicity. Processing the wool is similar to sheep wool and requires washing, although it doesn’t have the same heavy lanolin coating.

Producing a single sweater requires the output of 4 goats whereas a single alpacas can provide enough wool for 4-5 sweaters per year. All other wool providers, from sheep to alpacas, yield greater output per animal than goats.

There are organizations and companies that enforce very ethical and sustainable practices and even work toward enhancing the lives of the goat herders in remote areas. To help you find sustainable goods, look for:

- The Good Cashmere Standard (GCS)

- Sustainable Fibre Alliance (SFA)

- Gold Certification by WRAP

If you are set on the warmth and luxury provided by cashmere clothing, you probably shouldn’t expect to pay rock-bottom prices for a sustainable garment; look at is as an investment that will last many, many years.

Mohair is the product of Angora goat hair. Originally found in Turkey, the largest sources of Angora herd and mohair are now South Africa and Australia. Raising these goats puts the same type of stress on the environment as raising goats for the cashmere trade. Harvesting the hair differs. Angora goats are sheared twice a year, hopefully without harming the animal.

Overall, mohair is slightly more sustainable than cashmere, but only because it is more durable. Both goat hairs and compostable and biodegradable, as long as toxic chemical dyes haven’t been used.

Silk

Kim Taylor/Nature Picture Library

Source: Britannica

Silk is probably the oldest luxury fabric with a history that goes back to the early Neolithic age in China. Often, older fabrics like linen, jute, or hemp are very sustainable simply because they weren’t reliant on power and chemical means for production. Silk is an exception. It isn’t particularly sustainable.

The loudest complaint against silk is that the silk worms are almost always boiled alive in their cocoons so it can be easily harvested.

It takes about 3,000 cocoons to make a single yard or pound of silk. This isn’t the only reason silk is considered unsustainable. Large swaths of land are devoted to cultivating mulberry to feed the worms. 2,000 newly planted trees that have to be tended for 8 months in order to feed 20,000 silk worms the 500-600 kg of leaves they need to reach maturity.

Granted, mulberry is easy to grow and resistant to pollution, but it still requires a great deal of land and manpower. Fabric production requires large quantities of water and is very reliant on chemicals and heat, especially to dye the fabric. There are also issues of worker rights common to the silk industry.

If your objection to wearing silk is the ethics, there are some manufacturers who wait until the worms shed the cocoons naturally before processing them. Look for fabrics called “peace silk” or “ahimsa” silk. The resulting fabric is a bit coarser and less glossy than traditionally harvested silk, but the worms are treated ethically. If your concern is the chemicals used in production and dying, look for GOTS or OEKO-TEX certifications.

If you object to the use of silk worms but want a silk-like, strong material, there are a couple new of fabrics that are emerging based on lab-made spider silk. No actual living creatures are used in the process. At Qmonos™ spider silk genes are combined with microbes and fermented in sugar to create fibers that are 5 times stronger than steel and stronger than Kevlar, yet are lightweight, flexible, and biodegradable. Microsilk™ uses bioengineered spider genes that are fermented in water, yeast, and sugar.

Silk proteins are produced in the slurry, extracted, and spun into yarn. Microsilk doesn’t require the heavy chemicals to hold dye that silk does. Both fabrics are biodegradable and compostable.

Research continues into materials, especially plant-based waste materials, that can be used sustainably to mimic silk-like fabrics. For instance, there are currently groups in Italy exploring citrus fiber waste as the primary base for a new material.

Leather

There are many types of leather used in the fashion industry, though none of it is particularly sustainable. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2.29 billion cows, buffaloes, goats, and pigs were slaughtered to satisfy the demand of the fashion industry.

It’s easiest to limit this review to cow leather since that comprises the majority of the very large demand. As we’ve discussed with sheep and goats, the amount of methane released from that quantity of cattle is detrimental to climate change.

Additional methane and CO2 are created and released when the hides are transformed into usable leather. In addition to the ethical issues of animal cruelty and humane euthanasia of animals for their hides, there are the problems of overgrazing, feeding and watering, and the toxic waste produced in maintaining herds.

The most unsustainable aspect of leather is the tanning and processing of hides into usable leather.

Only 15-70% of every hide can be used, the rest is discarded as waste. While there are natural tanning processes that have been employed by different cultures, including vegetable tanning, 85% of modern leather is tanned using heavy metals such as chromium, formaldehyde, lead, calcium hydroxide, sodium sulfide, ammonium chloride, aldehydes, dyes, and PFAs or Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl substances.

These are carcinogenic and toxic chemicals that enter waterways and pollute the soil surrounding tanneries, as well as having severe health effects on workers.

Even if a tannery location is properly managed, there are stringent disposal methods for the chemicals used. In Kanpur, India, more than 400 tanneries have dumped toxic chromium into local water supplies. There are more than 100 tannery sites that have been identified by the Pure Earth Toxic Sites Identification Program, putting more than 1.8 million people at risk. The largest leather producing countries are China, Brazil, Russia, India, Italy, South Korea, Argentina, and the US.

Tanning is also water- and energy-intensive, and the VOCs from the chemicals used affect the air quality in the factory and its surrounding communities. Commercial large-scale methods of tanning leather affect the quality of the air, water, and soil. It’s important that the highest standards of waste management and environmental regulations be followed. To be sustainable, you can look for certifications such as:

- Zero Discharge of Hazardous Chemicals (ZDHC)

- Leather Working Groop (LWG)

- OEKO-TEX

- Sustainable Leather Foundation

More sustainably tanned leathers will be either vegetable tanned or water-based leather finished. Look for leather that is chrome-free. Recycled leather is another way to lower the impact of your leather purchases.

Leather Alternatives

Because leather has such a poor record, there are many attempts to find sustainable alternatives. The earliest depended on PVC plastic or polyurethane, none of which are in any way sustainable, recyclable, compostable, or comfortable. The same environmental issues that exist for other synthetic/polyester/plastic fabrics exist with faux leather or pleather. These just aren’t sustainable, although they may be more ethical because no animal products are used.

A variety of leather substitutes using plant or aquatic waste materials are being explored. Probably the most well-known and established is Piñetex™, made by Ananas Anam. The 40,000 tons of pineapple leaf waste that would otherwise be discarded are used to create the fabric. This is a far less toxic material than either the real thing or plastic-based materials.

There is also less waste during production than leather because the product is manufactured in uniform rolls instead of irregularly shaped and flawed hides. The manufacturers don’t use any additional water, fertilizer, pesticide or land than current food needs. Sustainability-wise, if new land is clear-cut to plant additional pineapple crops, the sustainability of the product could decrease and biodiversity would be impacted.

Other advantages to creating new products/leathers from agricultural food waste is that the raw materials won’t be left to rot or discarded in landfills. Selling the waste product also provides a secondary source in income for local workers and producers.

There are other plant-matter products that mimic leather in experimental-to-early small batch production stages. They also rely primarily on waste products from local food suppliers.

- Cork from the cork oak tree. The tree benefits from the bark being harvested. It is recyclable.

- Mushroom leathers. Mycelium, or mushroom skin, is being explored as the foundational basis of everything from leather (MycoWorks™) to building materials. This can be lab grown, and has a very small environmental imprint. It is biodegradable and compostable.

- Cactus leather is made from the nopal cactus, or prickly pear plant. The leading producer is Desserto. Mature pads or leaves can only be harvested twice a year. The plant is fast growing yet needs little water or pesticide use to thrive. Growing them is carbon neutral. The cactus isn’t harmed by the harvest, but at this point, only 600,000 linear yards can be produced per year. There is a fairly limited life span of 10 years for the finished product, but it is mostly biodegradable. There is a small amount of recycled polyester used in manufacturing.

- Malai, or coconut leather, is an organic and a sustainable bacterial cellulose product that uses the waste from the coconut industry. It is compostable.

- Discarded apple skins and cores are processed to resemble leather. The product must be backed and coated to be functional. Dependent on the materials used, the leather itself is compostable and another example of making use of agricultural waste. Frumat is the leading supplier of apple leather.

- VEGEA, based in Milan, uses the grape seeds, stalk, and skins discarded by nearby wineries to create a bio-based leather that doesn’t require toxic solvents, heavy metals, or chemicals. It has a polyurethane top-coat and cotton backing so it’s not currently biodegradable. It uses 78% renewable and recycled raw materials and organic cotton.

- Teak leaves are being layered with fabric and sealed to create a leather-like material. TreeTribe uses no harmful dyes and their products are organic.

- TômTex is a start-up that’s using shrimp shells, mushroom waste, and other biomaterials like coffee grounds to create a material that resembles leather. The product is completely biodegradable.

- Mango waste, transformed into leather-like material, is still in the developmental stage in the Netherlands, but shows promise.

These are just some of the exciting innovations that are being explored to decrease our dependence on either animal or plastic based leathers to find sustainable products that don’t require toxic chemicals. They also make use of food and plant waste keeping it out of landfills, thereby reducing methane and CO2 emissions.

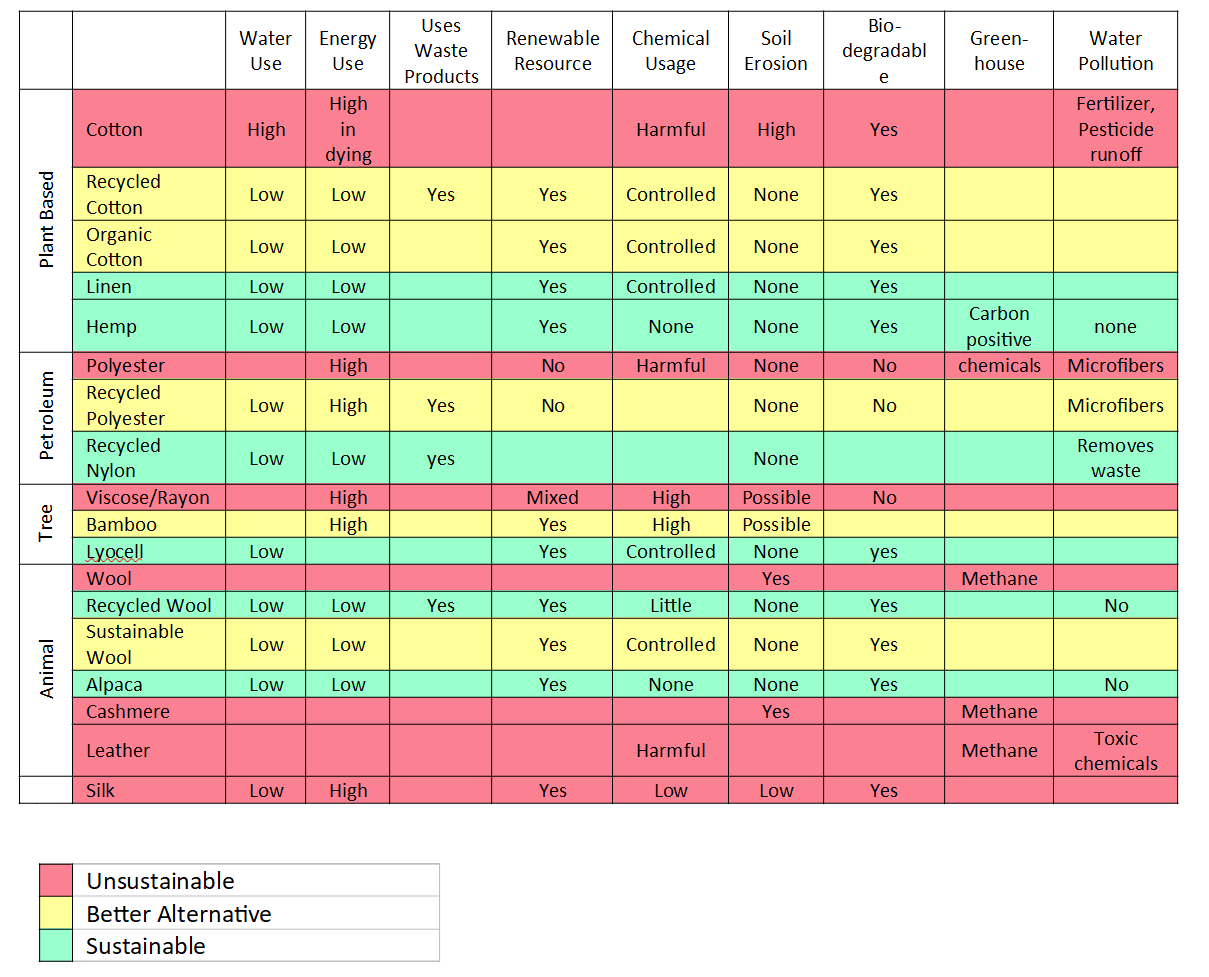

Fabric Sustainability At-A-Glance

Final Thoughts…

Fashion waste is a huge problem caused by a combination of choosing unsustainable fabrics, buying too much, and incorrectly disposing of it because there aren’t good recycling options.

We are buying more, quickly throwing it away, and falling into the trap that fast fashion sets that we need more and more. Because it’s cheap, we can just toss it and buy something else.

Fast fashion is using more and more resources creating demand by putting out 10 collections a year instead of two in their effort to continually sell you something new. The overstock and waste fabric from production are just dumped in deserts and landfills to molder for decades…or centuries… creating toxic dumps.

Exciting experimentation and research are going into how to use agricultural food by-products and waste to make sustainable fabrics to break this cycle.

Choosing carefully and thoughtfully, knowing how to care for the clothes you already own, buying fabrics that are biodegradable, compostable, and recyclable, and use fewer chemicals or non-renewable resources is key to controlling the run-away fashion industry.

Eventually, companies will start making more of what sells, and less of what doesn’t. It’s simple economics, with the consumer in control. Luckily there are many companies who have a corporate conscience and choose environmentally sustainable raw materials, manufacture responsibly, and treat their workers ethically. More and more companies are choosing this path.

It’s simple to help curb fashion’s runaway unsustainability:

- Buy less

- Know what is sustainable, and buy thoughtfully. Support companies you know are ethical and sustainable. Don’t believe greenwashing and look for reputable certifications.

- Care for your clothes correctly and keep them longer.

- When you are done, dispose of them properly – recycle, upcycle, or compost whenever possible.