This essay on the history and current state of ableism in architecture discusses the prevalent drive of regrettably key figures to ascribe standardized, or even divine, ratios to the human form, and subsequently to use these ratios in the design of homes and public spaces, much to the frustration of people who don’t fit into these standard models. The result has been discrimination by design; and yet, by becoming aware of this, the design students of tomorrow might find ways both practical and beautiful to overcome it.

By Azaan Rahemtulla

Abstract

The Modular Man was developed by Le Corbusier to integrate human form, architecture and beauty in a single system based on the proportionality of what he believed was the ‘ideal man.’ Le Corbusier was inspired by the Fibonacci series, as its purpose was using this golden ratio to maintain the human scale everywhere. He hence believed that through such found form, he would be able to easily understand and implement the idea of proportionality in his architectural practices. Even though architecture today has changed so much, it still incorporates the Fibonacci sequence and golden ratio to advocate for a myriad of people who all interact with architecture in their own way, especially people who are physically challenged, disabled or require wheelchair accessibility. These measurements have consciously and unconsciously been implemented as standards for building and are called guidelines, laws, acts and regulations.

The Modular Man was conceptualized under the assumption that the perfect dimensional basis for architecture is a 6-foot-tall white man. This ideology has evolved, and hence my ambition to redefine the Modular Man with consideration for equality in today’s milieu. Not only is the Fibonacci series apparent in architecture today, but there are also studies that indicate the evident traces of the golden ratio within wheelchairs, ramps and other rehabilitation aids – which relinks Le Corbusier and his thinking to present day social and political issues on accessibility services in architecture. Inclusivity is now taken into consideration through laws and guidelines ensuring easy accessibility for all, which consequently draws a new basis for modern architecture, or a new Modular Man.

A New Modular Man

Albert Einstein believed, “The Modular is a language of proportion that makes good easy and bad hard.”1 The Modular Man was developed by Le Corbusier to integrate human form, architecture and beauty in a single system based on the proportionality of a 6-foot tall healthy Caucasian – what he believed to be the ‘ideal man.’2 Intriguingly, there is evidence of the golden ratio in architecture today that advocates for not only the ‘Modulor’, but a myriad of people, all physically different, who all interact with architecture in their own way. This is especially true for those physically challenged, disabled or require wheelchair accessibility. Einstein failed to see that perhaps the good was made ‘too easy,’ and the oversimplification had created a gap discounting for a spectrum of equally important people. Architecture today cannot be based on Le Corbusier’s primary findings, but rather is dependent on laws and guidelines ensuring adequate accessibility for all, especially the physically disabled – which consequently draws a new rubric for modern architecture, a new Modular Man.

The Golden Ratio was the genesis that formulated the Modular Man, mirroring a blueprint by which all proportionality in architecture would be designed. Born by the Fibonacci series, from Vitruvius to Le Corbusier, mathematics and its ratios have been used to define and characterize architectural design.3 Le Corbusier sought dimensional proportionality in all things built, following the basis of the Fibonacci sequence and his ‘ideal man’ to govern architecture, as all things in nature were. Utilizing the golden ratio (1.618:1) to maintain the human scale everywhere, he believed that through such found form, he would be able to easily understand and implement relative proportionality in his architectural and urban practices. A modern endeavor to “embody harmonious proportions and a design philosophy according to which buildings derive from the human needs of the inhabitants.”4 Despite the underwhelming sect of the global population the figuration represented, Le Corbusier was initially inspired by Englishmen and other pop-culture, thus attempting to display how architecture was merely a byproduct of mass consumption.5

The beauty in the Fibonacci sequence is apparent in more than just human proportion, but in living animals, plants, architecture, hence embodying a particular aesthetic ability. For this very reason, it was entitled, ‘the divine proportion.’ 6 The Fibonacci series was then used to construct phi (Φ) or the golden rectangle, “the most pleasing proportion to human eyes.”7 To delve deeper, the ability for the Fibonacci series and thus, the golden ratio to derive a proportional base-drawing which would later govern architecture and its design is reiterated through time. From the Egyptian pyramids, Phidias formulating the design of sculptors in Pantheon, Notre Dame in Paris, to the United Nations buildings today contain traces of the ratio.8 More than for its visual aptitude, the golden ratio has also manifested a foundational facet that aids in a structurally sound and habitable space. Le Corbusier hence employed the Modular Man to design art, buildings, and cities meritoriously, even claimed to incorporate the ‘Modulor’ in planning his Unité d’Habitation apartment block in Marseilles.

However, Le Corbusier’s impression of the Modular Man is obviously flawed in today’s modern era. In a world so diverse, a simple drawing like the Modulor could not possibly define the politics in design mechanisms and their corresponding societal influences. Laws in accordance to Architecture Barriers Act of 1968 (ABA), amongst other various regulations, make it mandatory to build according to particular regulations and guidelines that adhere to all people, not only 6-foot-tall white males.9 It is evident that today, a vast majority of man-made designed environments have been built upon the capacity of the able-bodied, genuinely disregarding physical disabilities. Architecture that holds spatial and formal symbolic value; like the stairs of churches or government buildings are assumed to be monumental and hence indispensable, yet are forced to be redesigned by regulations to accommodate for the larger society.10 Such an environment encourages disabled people to demonstrate that they have abilities.11 While architectural qualities like service elevators and ramps are positively cherished by the physically disabled, they also prove to be valued by the entire society.12 Architecture appreciated by everyone recognizes the needs of the physically disabled, providing an impetus to design, thereby evident in becoming a new Modular Man.

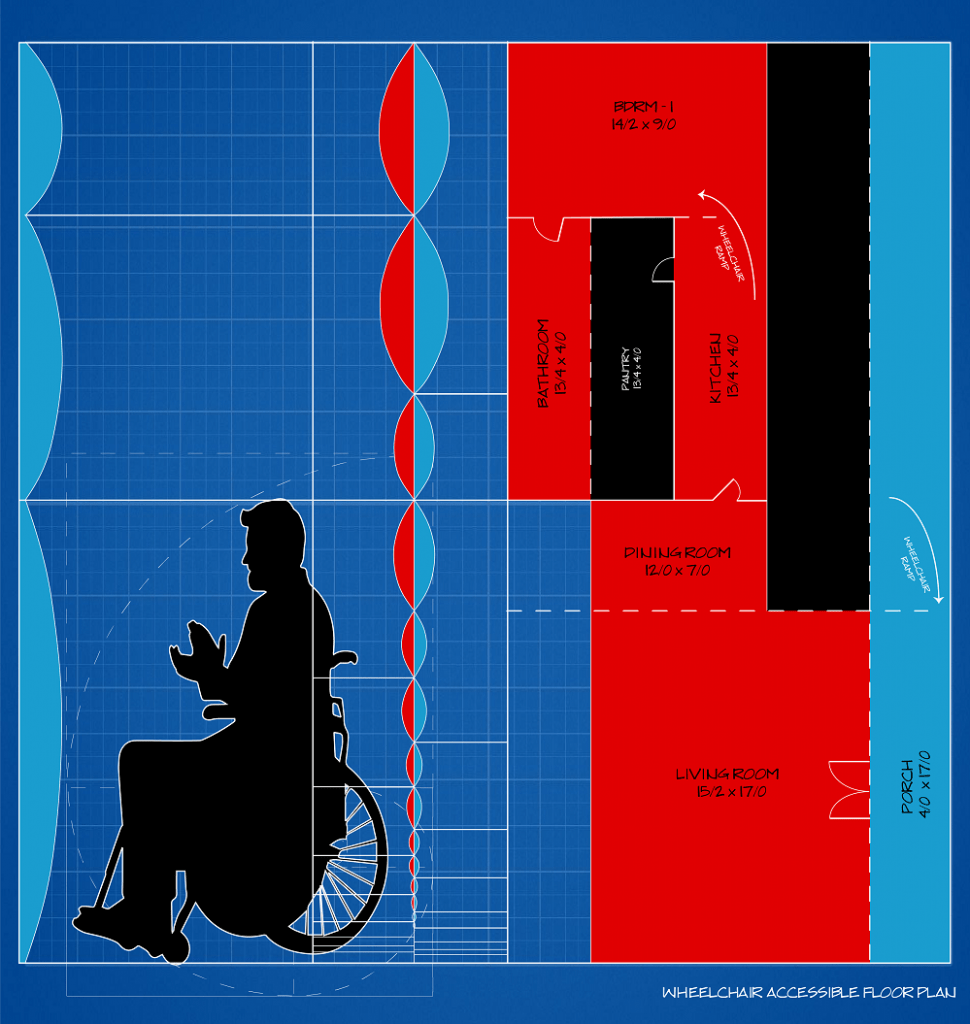

The actual laws and governing norms that dictate the way in which architecture is sought today advocates for wheelchair access, ensuring copious accessibility to all spaces. For wheelchair users, according to the American Society of Landscape Architects, factors compulsory to consider include: mobility, space, posture, reach, and strength.13 Mobility ensures for the angle of inclination in graded ramps, and to accommodate wheels, the surface must be both smooth and hard. Sufficient space for turning points, need to be at least 18″ x 12″, requiring an area of approximately five square feet.14 Posture takes into consideration what the wheelchair user has to perform from a seated position. Similarly, reach contemplates how eye-level is much lower than that of the average ambulant person. Strength inspects ideas like the effort needed to open heavy doors. To be able to understand the severity of these concerns, other laws including the Ontario guidelines express illegality in elevation from the outside ground floor to the main floor entrance being less than 7.84 inches. 15 (section 3.8 of the Building Code.) Regulations and other protocols like those by the ABA, enforce a code and building requirement that molds and reinterprets the architect’s initial design.16 Assuming Le Corbusier used the Modular Man to design the church of Sainte Marie de la Tourette today, his first iteration would be challenged by these laws so extensively that the initial design would be bound to transform entirely.

Furthermore, there are physical traces of the golden ratio in mechanisms that aid for accessibility. This provides an ironic rebuttal to Le Corbusier’s theory that while in fact both the Modular Man and engineered rehabilitation mechanisms are intuitively from the Fibonacci series, the physically disabled seem to author today’s architectural and thus technological milieu. The golden ratio (1:1.6) beautifully manifested in nature is also apparent and practical in engineering. As Le Corbusier has clarified, the human body personifies the golden ratio; one’s total height in relation to the distance from one’s hips to the ground. To further this notion, the human mind has perhaps subconsciously found this constant to be an attraction, as subtle reappearances psychologically contain a particular aesthetic. According to research by MIT, the length of a wheelchair is usually about 1.6 times the width of it.17 Even the door that fits the golden ratio has the most pleasing proportions. For an easy sliding cylindrical mechanism, one has to ensure the length in which they overlap is at least 1.6 times the diameter. The footrest clamp on the African-made wheelchair is extremely well intended, as the clamping cylinder “overlaps the frame tube by 3 times the tube diameter.”18 Whirlwind Wheelchair’s latest scheme, ‘Liviano’ looks exceptionally appealing because it has proportions very close to the golden ratio. “These proportions also make the machine perform well – the chair is well balanced and can easily climb over obstacles.”19 Taking all that into account, even ramps and elevators use this ratio. The ADA standard ratio is 4.8° incline per step 20, which is exactly 3 times the golden ratio. Therefore, beside actual laws and governing mechanisms in place, Le Corbusier’s initial thoughts and vested dedication in the Golden Ratio is an affirmation to a template of the physically disabled being the real Modular man, as the man then becomes part of the machine.

As modern architecture advocates for and encourages equality, there is augmenting indication in the infamous nature of the Modular Man. Some architecture is even specifically designed and produced for the physically challenged yet able to be appreciated by all, a situation unlikely to be reversed. According to WHO’s World Report on Disability, about 15% of the world’s population lives with some form of disability, that’s approximately 1 billion people, of whom 2-4% experience significant difficulties in functioning.21 For these billion people, it is easy to automatically feel unwelcome in most public spaces. “Le Corbusier is partly to blame … (he) created the fictitious character, Le Modulor —an able-bodied man, of average height and dimension, around whom he believed standardized design should revolve. Whole cities were designed by the able-bodied men on which Le Modulor was modeled.”22 An era of ignorance, highly distinctive from today where simple embellishments like ramps amplify exquisiteness and deliver necessity. Through various bylaws and protocols, several buildings today are particularly evident in a reconsideration for the physically disabled. As far as design is concerned, the reality of the situation is that when architecture is based on the physically disabled, it is excessively comfortable for all, made for everyone. For instance, a wheelchair user roaming the picturesque Ed Roberts Campus, professed “this was the first building he could move through seamlessly, without asking for any help.”23 Undoubtedly, a situation unravels where design allocates a sense of liberation for all users of the space unlike the suffocating by-product of the Modular Man where humans become a slave to the architecture.

The leap architecture has taken since the Modular Man is evident, entire buildings are now being tailored based on a discernible minority; the physical disability of being deaf or blind. A handicapped person is defined as an individual who has a physical, mental or emotional impairment making human performance unusually difficult.24 A case-study worth considering is DeafSpace, an institution that believes in architecture illuminating “a multisensory experience.”25 While designing a school, from the classroom in an open ‘U shape,’ to the width of ramps and stairways leaving ample space for sign-language communication. A sense of awe dissipates as light is diffused and directional to strategically help awareness. Mirrors echo attentiveness, enabling peripheral multidirectional vision. On the other hand, spaces created for the blind ponder the reliance on the sense of touch, heat, sound and balance.26 The Seehotel Rheinsberg in Germany, involves a facet incorporating tactility and technology in each room, exemplifying optimal ease and comfort.27 There are several examples of Architecture developed for the blind, but “great architecture for the blind and visually impaired is just like any other great architecture, only better, with a richer and better involvement of all senses.”28 The very idea that physical disabilities are governing brilliant architecture can thus be considered as a new rubric by which buildings are conceived.

Arguably, it was perhaps a coincidence that Le Corbusier was correct in his methodologies, as mass architecture is designed based on the average sized person in their respective country. Le Corbusier started his journey as an architect in Switzerland, and the average male’s height in Switzerland between the 1940’s and 1960’s was 181cm, which is in fact 5.93 feet.29 This hence attests to his thought process and advocates for his rationale yet does not suffice as enough to base entire buildings or cities on. There are several other ideas to consider, especially today in a space that negotiates relationships between notions of the modern self and the socio-technical setting in which this self is situated. Hence, inextricably, it is possibly because of the mind’s ability to find patterns in everyday happenstance (like the Fibonacci series) that made Le Corbusier believe that all architecture should be built on the idea of The Modulor Man for effective results. Verifying this theory, Anthony Antoniades, who interviewed Le Corbusier’s apprentices, said “Le Corbusier had no idea of mathematics, contrary to what he professed.”30 Researchers have also measured the dimensions of the Unite d’habitation and found discrepancies as the claimed golden ratio subunit dimension (1.618) is highly improbable, the minimum possible scaling ratio being 2.31

The Modulor lacks truth and impartiality perpetuating a “cultural otherness from the raw materials of human physical variation.”32 Despite the fascinating ideology behind the figuration, Le Corbusier’s downfall is in accounting for bodily disparities that we now call ‘race,’ ‘sex,’ ‘weight.’ Being anything but the Modulor invokes inferiority, “a system of compulsory human values is set; able-bodiedness, whiteness and maleness.” 33 Hence postulating a condescending false premise for uncontrollable human betterment triggered by modern architecture itself. The polar opposite of the welcoming and equally accommodating homeliness embedded in its potential. Various boards of directives including; the Ontario Building Code, The ADA, amongst others, enforce laws that administrate, limit and broaden the method by which architects conceptualize designs. That, coupled with the new order and use of the Golden ratio now seen in the engineering of rehabilitation mechanisms that aid in accessibility constitute for a new Modular Man. That said, this new dimensionality inevitably morphs the lens through which architects perceive design.

About The Author

Azaan Rahemtulla is an aspiring architect, who’s main focus is using facets of parametric and adaptive architecture to propagate equality through human-centred-design. He has a strong passion for designing inclusive spaces sustainably that enrich the users’ liveable experience.

Connect with Azaan

Works Cited

“Architecture & Design for the Disabled People.” Arch2O.com, March 1, 2020. https://www.arch2o.com/architecture-design-disabled/.

“Architecture for the Blind: LightHouse Renovations Take a Leap Down the Path.” Arch2O.com, February 23, 2020. https://www.arch2o.com/architecture-blind-lighthouse-renovations/.

“The Rise of Deaf Architecture.” The Washington Post. WP Company, September 12, 2019. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/magazine/wp/2019/09/12/feature/the-rise-of-deaf-architecture/.

“World Report on Disability.” World Health Organization. World Health Organization, October 16, 2018. https://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/report/en/.

Arellano, Mónica. “On the Dislocation of the Body in Architecture: Le Corbusier’s Modulor.” ArchDaily. ArchDaily, September 27, 2018. https://www.archdaily.com/902597/on-the-dislocation-of-the-body-in-architecture-le-corbusiers-modulor.

Axis Architecture. “Design for the Blind: Architecture for the Visually Impaired.” Axis Architecture, June 5, 2018.

Bartolacci, James. “Architecture For All: 10 Thoughtfully Designed Buildings for People With Disabilities – Architizer Journal.” Journal, January 8, 2019. https://architizer.com/blog/inspiration/collections/design-for-disabilities/.

Craven, Jackie. “Designing for Everyone Is a Building Philosophy.” ThoughtCo. ThoughtCo, December 8, 2019. https://www.thoughtco.com/universal-design-architecture-for-all-175907.

Failed Architecture. “’Human, All Too Human’: a Critique on the Modulor.” Failed Architecture. Accessed April 21, 2020. https://failedarchitecture.com/human-all-too-human-a-critique-on-the-modulor/.

González, María Francisca. “Architecture for the Blind: Intelligent and Inclusive Spaces for the Blind User.” ArchDaily. ArchDaily, August 15, 2019. https://www.archdaily.com/923028/architecture-for-the-blind-intelligent-and-inclusive-spaces-for-the-blind-user.

Harris, Johnny, and Gina Barton. “How Architecture Changes for the Deaf.” Vox. Vox, March 2, 2016. https://www.vox.com/2016/3/2/11060484/deaf-university-design-architecture.

Nonko, Emily. “How Wheelchair Accessibility Ramped Up.” The Atlantic. Atlantic Media Company, June 23, 2017. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2017/06/ramps-disability-activism/531273/.

Ojo, Samuel. “Design Tools for Providing Wheelchair Access,” n.d. https://doi.org/10.31274/rtd-180813-7438.

Rühli, and Pfister. “The Average Height of 18- and 19-Year-Old Conscripts (N=458,322) in Switzerland from 1992 to 2009, and the Secular Height Trend since 1878.” Swiss Medical Weekly. EMH Media, July 30, 2011. https://smw.ch/article/doi/smw.2011.13238.

Salingaras, Nikos. “Applications of the Golden Mean to Architecture.” Architecture’s New Scientific Foundations, April 5, 2020. https://patterns.architexturez.net/doc/az-cf-172604.

Shekhawat, Krishnendra. “Why Golden Rectangle Is Used so Often by Architects: A Mathematical Approach.” Alexandria Engineering Journal. Elsevier, April 3, 2015. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1110016815000265.

Slessor, Catherine. “AR Issues: Redefining Modulor Man for a New Era of Inclusivity.”

ArchDaily. ArchDaily, October 3, 2014. https://www.archdaily.com/553365/ar-issues-redefining-modulor-man-for-a-new-era-of-inclusivity.

Thomson, Greg. “Accessing Accessibility Under the Building Code, the AODA and the OHRC.” Accessibility for Ontarians with Disabilities Act (AODA), June 4, 2017. https://www.aoda.ca/accessing-accessibility-under-the-building-code-the-aoda-and-the-ohrc/.

Tricker, Ray, and Samantha Alford. Building Regulations in Brief. Butterworth-Heinemann, 2011.

Winter, Amos. MIT. “Mechanical Principles of Wheelchair Designn, 2005. http://web.mit.edu/awinter/Public/Wheelchair/Wheelchair%20Manual-Final

Footnotes

1 “The Modulor.” The Modulor.

2 Failed Architecture. “’Human, All Too Human’

3 Slessor, Catherine. “AR Issues: Redefining Modulor Man for a New Era of Inclusivity.”

4 “The Modulor.” The Modulor.

5 Arellano, Mónica. “On the Dislocation of the Body in Architecture: Le Corbusier’s Modulor.”

6 Shekhawat, Krishnendra. “Why Golden Rectangle Is Used so Often by Architects: A Mathematical Approach.”

7 Shekhawat, Krishnendra. “Why Golden Rectangle Is Used so Often by Architects: A Mathematical Approach.”

8 Salingaras, Nikos. “Applications of the Golden Mean to Architecture.”

9 Ojo, Samuel. “Design Tools for Providing Wheelchair Access,”

10 Ibid.

11 Craven, Jackie. “Designing for Everyone Is a Building Philosophy

12 Ojo, Samuel. “Design Tools for Providing Wheelchair Access,”

13 Ojo, Samuel. “Design Tools for Providing Wheelchair Access,”

14 Ibid.

15 Ojo, Samuel. “Design Tools for Providing Wheelchair Access,”

16 Thomson, Greg. “Accessing Accessibility Under the Building Code, the AODA and the OHRC.”

17 Winter, Amos. MIT. “Mechanical Principles of Wheelchair Designn, 2005.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Thomson, Greg. “Accessing Accessibility Under the Building Code, the AODA and the OHRC.”

21 “World Report on Disability.” World Health Organization.

22 Nonko, Emily. “How Wheelchair Accessibility Ramped Up.”

23 Nonko, Emily. “How Wheelchair Accessibility Ramped Up.”

24 Ojo, Samuel. “Design Tools for Providing Wheelchair Access,”

25 “The Rise of Deaf Architecture.” The Washington Post.

26 Harris, Johnny, and Gina Barton. “How Architecture Changes for the Deaf.”

27 Axis Architecture. “Design for the Blind…”

28 Ibid.

29 Rühli, and Pfister. “The Average Height- Switzerland.”

30 Salingaras, Nikos. “Applications of the Golden Mean to Architecture.”

31 Ibid.

32 Failed Architecture. “’Human, All Too Human’: a Critique on the Modulor.”

33 Ibid.