Governments must use knowledge gained during this crisis to plan a more sustainable future, one that empowers everyone to use streets healthily and freely.

Written by Ashita Parekh and Stuart Hamre

The window of opportunity

By now, nearly everyone around the world is witnessing the impacts of our collective social distancing and self-isolation efforts. People are travelling less—far less. Emissions from the transportation sector are falling, improving water, air, and overall environmental quality as a result.

We are experiencing what may be the start of a long, slow change in local, regional, and global mobility patterns. Cities are moving into lockdown remarkably quickly, and the socio-ecological impacts that result from our collective reduction in movement are being felt around the globe. In the coming months, as cities exit lockdown, it is important that we maintain and grow the benefits that have been realized by quick-thinking municipal staff and the general public.

What has been good for air quality has been equally good for pedestrians, cyclists, and transit operators. In short, having fewer cars on city streets has presented a preview of what life might be like in a future where space is allocated more equitably for all road users. The goal for planners and policy-makers should be to maintain some of these benefits we have begun to see on a permanent basis, once life begins returning to normal. The window of opportunity is rare and will be brief, and now is the time to act.

Learning from our collective situation

So, where to begin? Well, we can look at what’s already happening on an ad-hoc basis on many city streets around the world and start to formalize these changes.

One major and instantly-visible change in many cities has been the quietness of curbsides in once-busy commercial districts, which have typically been devoted to parking. They now lay empty for most of the day, apart from quick stops by take-out diners and delivery drivers. In response to increased delivery traffic, cities like Raleigh and Seattle have already begun turning spaces previously devoted to parking into temporary pick-up and drop-off areas to serve nearby businesses.

This shift from parking to pick-up and drop-off uses is likely to prove useful in the long-term as the transportation network enters the autonomous future. Today, increased use of ride-hailing and delivery services is putting pressure on curbside spaces. In the future, autonomous vehicles will also compete for curbside space. Maintaining the flexibility that temporary pick-up and drop-off areas have allowed would serve not only cities’ immediate needs during the pandemic, but support the long-term shift in patterns of urban mobility and freight movement.

Of course, urban streets serve many more people travelling on foot, bicycle, and transit than by car, and in a fraction of the space. At the same time, social distancing requirements have made it difficult to enjoy outdoor activities. Narrow sidewalks and bicycle lanes in many areas make keeping two metres between you and the person walking or cycling next to you impossible.

In response, some cities are turning traffic lanes into major active transport corridors. Two cities leading the charge are Bogota and Mexico City. New active transport facilities offer space to people who might otherwise need to ride crowded public transit, helping reduce the risk of virus transmission. In San Francisco, the closure of a main road through popular Golden Gate Park has been enforced to allow enough space for all pedestrians and cyclists to pass each other with ease.

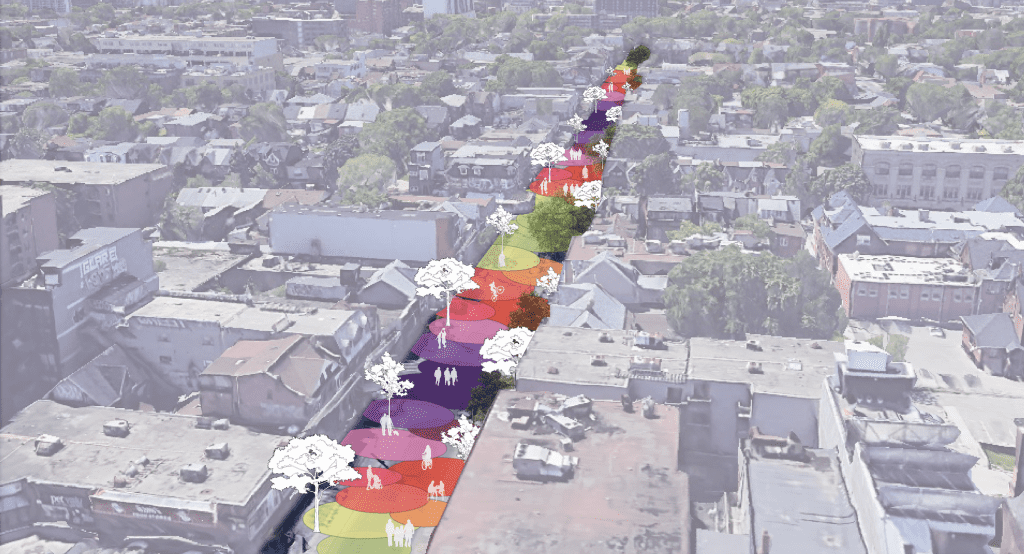

What proves useful for social distancing by giving cyclists and pedestrians more space and reducing transit overcrowding can lay the framework for pedestrianizing streets.

In North American cities, there is a great deal of redundancy in the road network, when it comes to vehicle accessibility. Most cities have only a handful of routes that are closed to regular vehicle traffic. Plenty have none at all, or restrict vehicles only during certain periods like “Pedestrian Sundays” in Toronto’s Kensington Market. Now is the time to turn streets over to pedestrians, limiting traffic to specific times of day or for specific purposes, like deliveries.

Pedestrian-friendly streets encourage people to walk, but also to sit and relax. When businesses reopen following the pandemic, they will be desperate for customers. By transforming local hotspots into welcoming spaces, cities can ensure that businesses get the attention they need by making streets safe, comfortable, and fun.

Moving forward

The speed at which local governments have been able to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic with shifts in urban operations has been remarkable. With concerted effort, many of these positive changes can be made permanent, thereby having a lasting impact on human and environmental health. Today, and as countries emerge from the pandemic, all it will take to realize the benefits we have seen in recent weeks is the will to learn from our collective change in behaviour.

Most importantly, the planning possibilities that present themselves to us in these uncertain times are cost effective, and many are operational changes only. Governments must seize this opportunity to move beyond “planning normalcy” to something that empowers everyone to move more healthily and freely—for the benefit of individuals and the planet.